After Belonging, or A Few False Starts: On Asa Drake’s Maybe the Body

In her 2021 exhibition, “her demilitarized zone,” Filipino-American conceptual artist Gina Osterloh has a striking self-portrait, “Mirror Woman.” The image features Osterloh covered in a skin of reflective tape, the new shell around her at once protective, alien, parasitic, beautiful. Her eyes seem to have vanished, her mouth and nose barely legible. The notion of portraiture is undercut by what seems to be a deliberate effort to obscure. Camouflage makes scrutiny fruitless or, at the very least, bi-directional. “I covered my torso and face, including orifices of the auditory, speech, and sight to conjure contradictions embedded in ‘borders’—boundaries between self and Other, and potentially national borders,” Osterloh writes. “Mirror Woman activates how a viewer may determine who belongs and who is considered alien.”

It’s this idea of belonging measured against the gaze of others that feels so trenchant in Asa Drake’s debut poetry collection, Maybe the Body. Fitting too that Drake turns to Osterloh as the source of one of two epigraphs for the book: “It was helpful for me to understand camouflage as, not a tactic of war, but a way in which a body can occupy an out-of-body space.” Similarly to Osterloh, Drake assembles a space where the body embraces camouflage, reflection, escape, inspection in turns. Maybe the Body is a book about the body, yes, and the ways in which the body is shaped by the force of a country, of an inheritance, of the labor of both beauty and devastation. But it’s also a book about how to endure in a world, in a country, in a moment where your grief will not be recognized and your archive will not be protected. For Drake, poetics that keep these conditions in mind must embrace the guidance of kin, allies, and oppressors alike. And it must be done by first excavating the implications of omission—whose history gets eclipsed by the reach of empire?

When I started writing about Maybe the Body, I emailed some questions to Drake. She said to me: “Shoutout to poet and philosopher E. Hughes… for recommending the work of Saidiya Hartman who introduces the possibility of critical fabulation, the possibility that we might listen for ‘the unsaid, translating misconstrued words, and refashioning disfigured lives,’ and out of such attention offer a truer record… I would like to imagine the body without an audience, but my experience is that my body is too frequently cataloged into narratives I haven’t chosen for myself. Perhaps the parallel question to what else is the body is what else am I.”

What is a body without an audience? Drake gives us this and, also, a body with an audience of so many different varieties that the body cannot help but shapeshift constantly. The title of her collection is, after all, maybe the body. Imbued in that single word is so much slipperiness and a sense of possibility that courses through the whole collection. The possibility of harm, of beauty, of collapse or endurance. Body as treasure. Body as spectacle. Body as object. Body as record. Body as archive. Body as wildness. Body as animal. Body as silence. Body as scream.

What renders possibility such a powerful poetic force in Drake’s hands is the way in which it is so duplicitous. History and language are not solely failures. Sometimes, as Drake writes in “I Worry My Mother Will Die and I Will Know Nothing,” “history is too beautiful to be believed.” And in our email exchange: “What is it, to want that which may be annihilated, between years of annihilation?” Indeed: How do we make space for both righteous anger and riotous celebration of beauty?

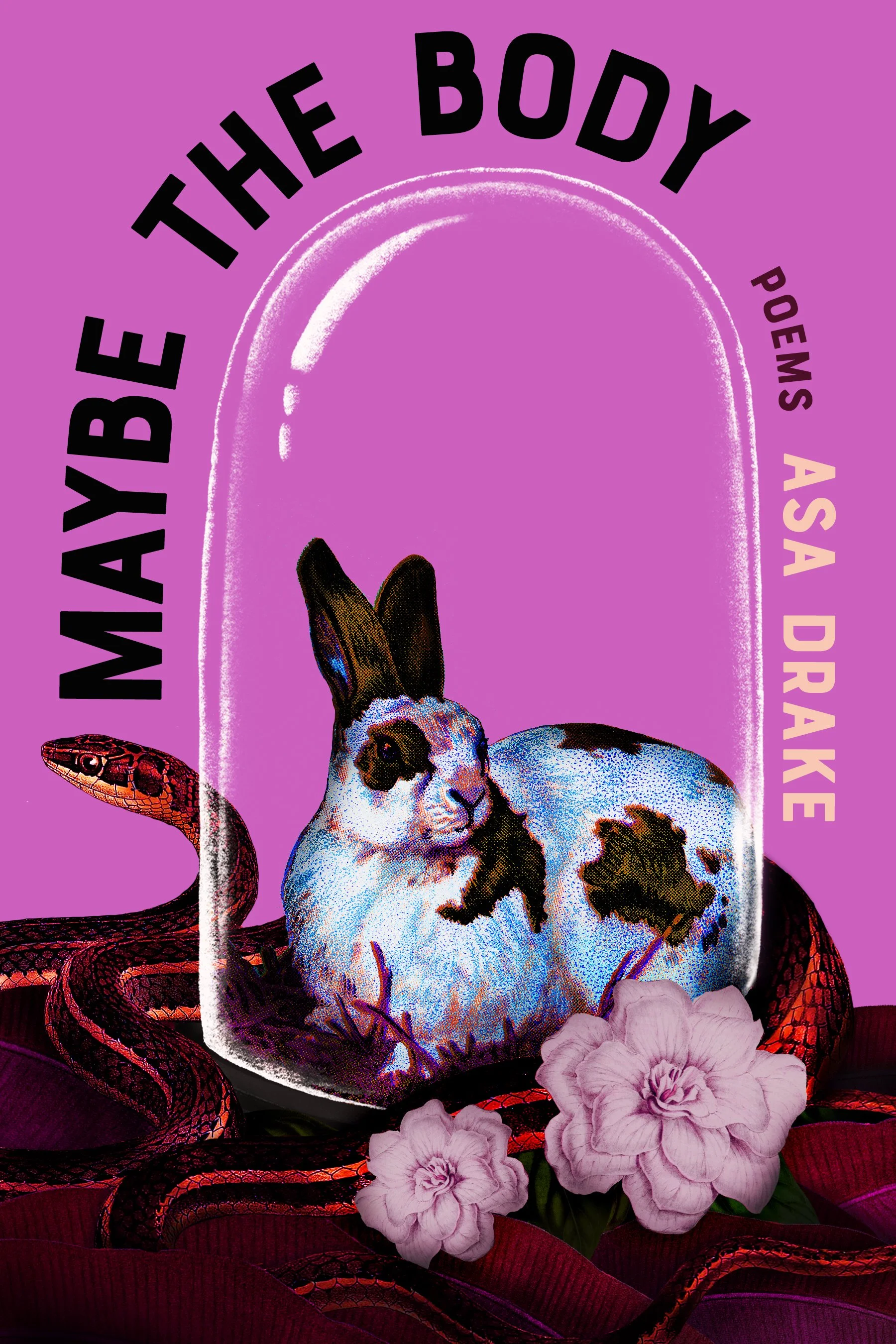

This, too, is everywhere in Maybe the Body: in the verdant images of pomegranates and toyo, loblolly pines and cherry blossoms, gardenias and the powder on plums, lizard mouths and rabbits that make their way even to Maybe the Body’s cover art. Here, a white and brown rabbit is enclosed inside a glass dome. Is it being preserved by the glass? Protected? Entrapped? Can holding onto a wild animal say something about both our capacity to love and our capacity to misuse? “Belonging demands being caught in one another’s border,” Drake writes. And when I read this, I thought, again, about Osterloh and the meaning of a border. How tender the line between keeping and containing. How there can be both comfort in standing at the edge of something and a fear enforced upon it. A location of immense perspective and a location to rehearse exclusion.

I want to believe the body’s evolution is not contingent upon external forces, but that feels like a fruitless desire. Then again, it feels that much of Maybe the Body is also about coming to terms with fruitless desire.

* * *

Once, I went on a walk with a friend through the city. He spent a solid twenty minutes pointing to all the different types of light: the taillights in traffic, the LED lights on a falafel truck marquis, the stoplight, the pedestrian light, the lighters strangers kept passing to each other, lighting stray cigarettes, brief diamonds of white flickering in the afternoon sun’s garish glow. “It really is the city of lights,” he said cartoonishly. Earlier, I’d been reading about the map they made of all the shadows in New York City. “The Struggle for Light and Air in America’s Largest City,” they’d headlined an article on the study. They described the dark veins of Broadway, sun-dappled shoulders of Midtown, a time-lapse view of Madison Square Park where buildings became sneaky ghosts through their passing shadows. Suddenly, light—or its absence—an animator.

A few years later, that same friend died and I went to his memorial.

Somehow, I ended up talking to someone he’d known since middle school. “Strange,” she said to me, “how, at the end, he felt like such a stranger.” And then, a few minutes later, offhandedly: “I guess intimacy is like joy—it’s not a neon sign. No easy way to get to it. No way to know you’re walking towards it.”

In the backyard: an herb garden along the edge of the house—browning mint and rosemary and basil leaves. I remembered him joking with me about it on the phone. He’d wanted so badly to grow a garden. But the shadow of the house took too much sun, and nothing really flourished. “It’s kind of beautiful though,” he’d said. “That reminder of things that tried to grow in spite of it.”

In Maybe the Body, Drake writes: “The heart / is a list of demands / I answer one by one.”

The body is full of attempt without the guarantee of resolution.

* * *

If we think about a border, it’s hard to not also consider a country, to consider the America of Drake’s collection. This America is one in which “More Than Half of Americans Can’t Name an Asian-American.” It’s an America where Drake’s speaker cannot disentangle questions of nationality from questions of possession: “It is possible what belongs to me doesn’t dictate where I belong.” It’s one where the news “hesitates to mention hate after the gunman’s confession. They recount a man lashing out as police insist on his insistence, he has not targeted victims, six of whom were of Asian descent, because of their race.” It’s one where the instability of language both enables expression and enforces constraint, particularly for bodies read through the narrow optics of white American nationality. To be legible, in these poems, is rarely to be understood. It is more often to be measured, categorized, or conscripted into narratives that precede the self. The body is forced to negotiate meaning in a language that is already suspicious of it: “I have heard someone I love speak around someone I love, like English is a sieve for catching one another’s cruelty,” Drake writes in “Tonight, a Woman.” The calculus of loss is quite similar to the calculus of beauty: the larger it is, the more you struggle to bear its weight.

In the same email I sent to Drake, I asked other questions. The body feels so multiple to me while reading that I wanted to know: How does she understand the body in the book? As archive, battleground, witness, instrument, or something else entirely?

“Over the course of writing Maybe the Body, I gave myself permission to step away from the assumption that I have a responsibility to make myself legible to others,” Drake told me. “The ‘illegible’ poem is often described in opposition to the ‘accessible’ poem. And the more I explored the distinction between the two, the more I wanted to confront what it means when accessibility, a word meant to offer greater equity, is used in this context to force visibility and digestibility for an unidentified, but presumably white, audience.”

This confrontation feels responsible, in part, for the formal variety in the collection. There are repeated modes of self-address (“Letter to My Younger Self,” “Dreamscape Dressed in my Younger Self”) as well as repeated moments of external address (“To someone who’s heard, I love you, too many times” is a title that recurs in each of the book’s six sections). And there is also a “we,” an “us,” a shifting “you,” and an address to the speaker’s mother, to Lolo Ahas, to Nanay, in turns. What results is an intensely collaborative collection where the public and the private become porous spaces and generous vulnerability informs self-protective guards: “Desire, not curiosity, / charts my migration,” Drake writes. “This is the part of me I must show everyone first.”

* * *

I think of my father. About how he discovered a cassette tape recording of a conversation he had with his favorite Washington D.C. disc jockey when, in a feat of complete magic, the station put him through to chat on air. “This was my absolute hero,” my father explained, loading the tape. His shows kept him company while he worked the night shift at the 7-Eleven as a brand-new immigrant—his English broken, his accent thick.

On the recording of the tape, I could hear my father’s boy-voice. Wonderstruck. Excited. But the more we listened to the recording, the more he realized something he didn’t realize when he first called in: The disc-jockey was mocking his fractured English relentlessly. At one point, he asked him to repeat the same sentence eight times before my father realized it was just a test to see how many times he would repeat it before he caught on.

My father stopped the tape. “My hero,” he laughed acidly, “was kind of a dick, huh?”

* * *

If we return to considering belonging—and the question of how we both define and search for this is maybe a rallying cry of Maybe the Body—the collection’s polyvocal effect draws attention to the voices who have been asked, too often, to self-translate or to silence themselves altogether. Identity is something not just shaped by who is afforded the chance to speak but by who embraces the human responsibility to listen.

The force of this lyric might eventually deposit us in a place where the notion of what comes after is still, against all odds, a liberating possibility. Aftermaths and afterimages and shadows and remnants scatter throughout the book.

Asa Drake returned an email in which I asked her why there are so many moments of “after” in Maybe the Body. Aftermaths. Afterimages. Shadows and remnants and echoes and fragments of history scattered all throughout the book. She described to me how her interest in after-hood is due largely to a distrust in the nature of explanation itself. “I can’t remember where I read this, but a poetry edict that has resonated with me is that ‘poetry is not concerned with because,’” Drake said. “‘Because’ is a logical structure that has failed me. But ‘after’ offers me something much more open. Something always happens next—even if it doesn’t happen to me.”

I am the granddaughter of a woman who told me, once, that “the world is full of rooms that never had a place for us.” Her America was an America that regularly strip-searched her son at airports just because of his last name. She came to America because America gave her country away to a new state that would, for decades, continue to bomb her people. Her America was an America that did not care for the safety of her body, only its tacit need to be surveilled and policed.

Her America is an America that taught her vigilance through force and fear, that doles out its welcomes ungenerously and impermanently. What can you do to earn a sense of belonging in America? For people like my grandmother, this question is fundamentally linked to another: What must you give up to earn a sense of belonging in America?

* * *

When I love something, I find it easier to write alongside it rather than about it. This is true especially of Maybe the Body, not just because it is a book that offers so much to love—precision of language, a deeply embedded sense of both narrative and lyric devotion, the killer cover art—but because it is a book that feels like an invitation to converse.

“I like to watch videos of this aging rabbit on Instagram being hand-fed parsley // and sliced apples,” Drake writes, “because of what this implies about our capacity / for love. This skin-mottled body, kept.”

* * *

I begin making a list of all the states of “after.” After collapse. After loss. After silence. After song. After our loved ones become ancestors and our joys become memories. Sometimes, dwelling within the present feels incredibly untenable. After is a way of looking not so much to the future but of searching for some motivation to endure. That whole this too shall pass maxim sometimes leaves me feeling guilty, as though I am looking away from a present that, in demanding accountability, demands witness. To look towards after, however, feels like an understanding that the work will continue. In that sense, Drake’s fascination with things that grow—flora, fauna, memory, calyx, redwood—makes sense to me.

The gaze in her collection extends in so many directions. The past, the present, the afters are places, not just moments in time.

* * *

Once, a woman came into my father’s restaurant and asked him what kind of Arabic food they served. “Is it the food of good Arabs,” she asked. “Or is it the boom-boom Arabs?” He didn’t know how to respond. “It seemed strange,” he told me, “that she was willing to admit the possibility of good Arabs.”

In Maybe the Body, Drake writes: “(Yesterday, a man who voted against integration told me I remind him of his wife, a real lady. Still, I helped him…)”

* * *

Maybe the Body is a book about the difference between desire and curiosity.

* * *

To say the space of an “after” is a space of hope feels reductive. Instead, it might be more fitting to think of it as a space of belief. Of choosing to believe.

When I began reading Maybe the Body, I began another list. In addition to my list of afters, I kept a running list of all of the things it seemed the book was about. The list grew increasingly unruly: Maybe the Body is a book about having vs. halving; Maybe the Body is a book about wreckage; Maybe the Body is a book about how it feels to want impossible things; Maybe the Body is a book about “letting the animal in”; Maybe the Body is a book about the sound ice makes when it’s falling in your glass because it’s a book about being attentive to a world in which no sound, no sensation, is ornamental. The multiplicity of “aboutness” is exactly what makes the book feel so unyieldingly beautiful. Just as it makes the project of describing it so difficult.

* * *

When I woke up to news about the United States kidnapping Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro, I returned to a set of lines in Maybe the Body: “Remember, America is only one possibility… // There are a million things you can halve in the world. A million you can’t.” In that homophone “halve” (which one might read, at first, as “have”) we understand that for everything we are capable of building, we are capable of breaking. And everything that has the capacity to break also has the capacity to be broken. When you look towards one thing, you look away from something else.

A few days later, a friend wrote to tell me she’d just gotten engaged. The joy was buoyant. Again: States of simultaneity stack up. We shove devastation so close to hope that I think, sometimes, we wonder if they will cross-pollinate.

* * *

In “The World Begs for Transcription,” Drake writes: “Beloved, if it is the year of the comet, do not look for the comet.” I’m thinking, in this way, of the refusal of light. Of how, any time you look towards one thing, you look away from something else. How deciding not to search is a way of searching elsewhere and this state of elsewhere, also, to me, feels like light.

I’m also imagining the other end of that directive. If one does not look for the comet, what does one look for?

* * *

Maybe the Body is a book about what it means to speak English.

* * *

If we return—one last time—to the notion of belonging, maybe it’s more fitting not to describe what Maybe the Body is about, but who Maybe the Body belongs to: anyone who has ever felt alien—legally, corporeally, permanently, ephemerally. Anyone who has doubted their country’s ability to hold up the weight of their loss or their forgiveness or their joy. Anyone who has had a family member who has ducked their head in shame when their pronunciation of a word was publicly corrected. Anyone who has stayed up at night worrying about the responsibility of keeping their culture, their stories, their people alive. In this sense, Maybe the Body is also maybe a love letter. Maybe an act of crucial witness. Maybe an act of validating one’s right to both denounce the violent syntax of a country’s governance and to praise the beautiful rabbits, the amber calyx, the coastal redwoods that also call it home.

The irony is not lost on me that this book has so many moments about the nature of labor and work (moral and capitalistic) and, as a result, is a book that does so much work itself. Which is really my way of saying that, as I read and re-read, I still couldn’t help but make a running list of all the things you could say this book is about. Chief among them: In both its work to scatter and accrete, to tender the boundary between public and private, self and other, this book feels like an elegy for wholeness. “To say we love the unrelenting / aspects of the world and carry them with us // into its aftermath, which is full of potential. / You are rebuilding the garden someone taught you / to love,” Drake writes. It feels like an invitation to remember: Every day, the body shows us the ways that it can empty; but there is something worth paying attention to in the ways, also, it contains.

A.D. Lauren-Abunassar (@lauren.abunassar) is a Palestinian-American writer, poet, and journalist. Her work has appeared in POETRY, Narrative, Rattle, Prairie Schooner, Boulevard, and elsewhere. Her first book, Coriolis, was winner of the 2023 Etel Adnan Poetry Prize. She is a 2025 NEA fellow in poetry.

Asa Drake (@asaldrake) is a Filipina/white poet in Central Florida. She is the author of Maybe the Body (Tin House, 2026) and Beauty Talk (Noemi Press, 2026), winner of the 2024 Noemi Press Book Award. A National Poetry Series finalist, she is the recipient of fellowships and awards from the 92Y Discovery Poetry Contest, Kenyon Review Residential Writers Workshop, the Rona Jaffe Foundation, Storyknife, Sundress Publications, Tin House, and Idyllwild Arts. Her poems are published or forthcoming in the American Poetry Review, Georgia Review, and Poetry. A former librarian, she currently works as a teaching artist.