Motherhood Is a Bitch: A Review of Nightbitch

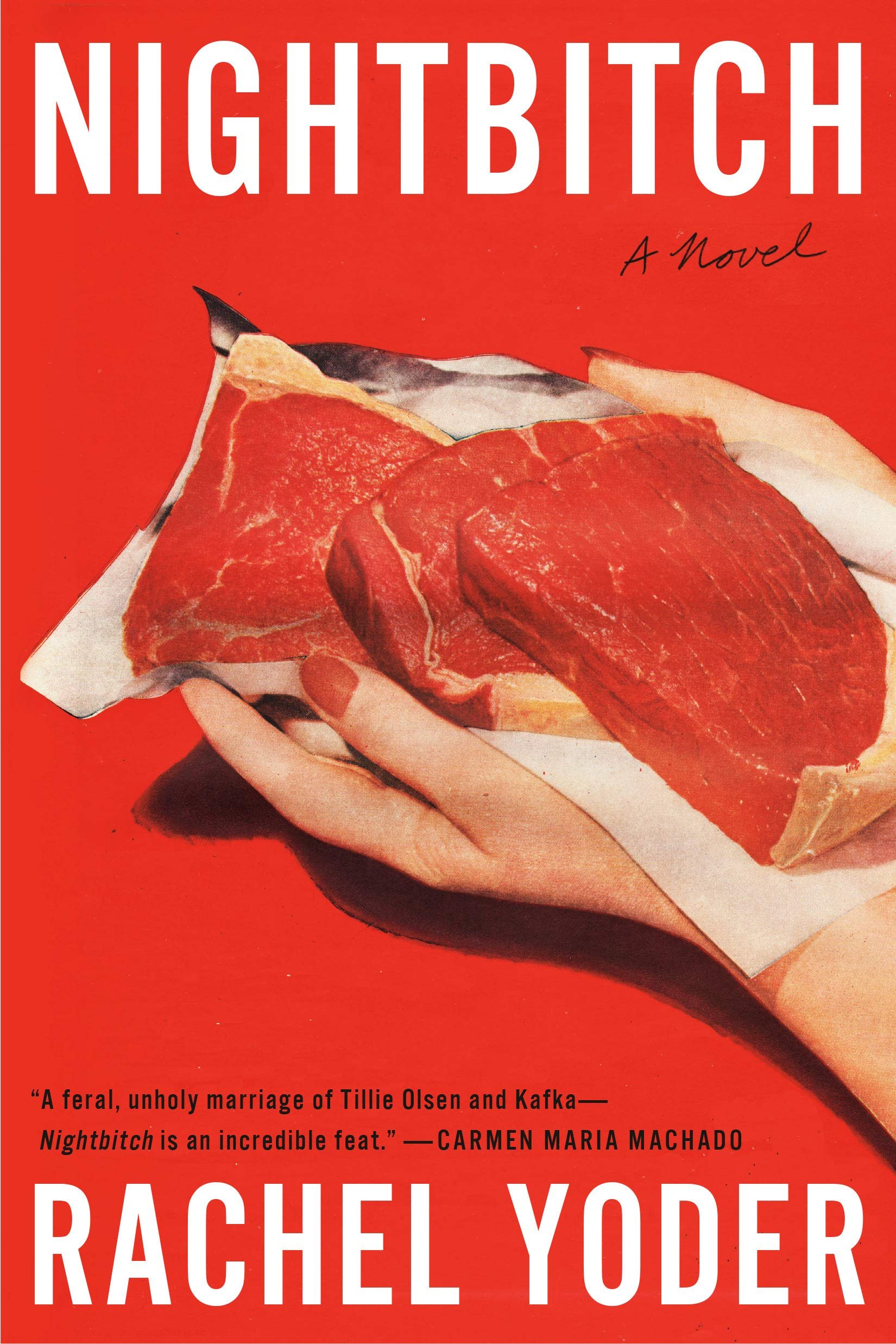

Nightbitch

By Rachel Yoder

July 2021

Doubleday

ISBN: 978-0385546812

256 pages

Reviewed by Erin Flanagan

Portrayals of motherhood have a long history in literature, as do people turning into animals to escape the shackles of their gender roles and societal norms (Enid Shomer’s story “Laws of Nature” comes to mind, as well as most portrayals of werewolves). But what makes Rachel Yoder’s debut novel Nightbitch such a standout is its raw and often hilarious honesty, its stunning ending, and its focus on creation both through biology and art.

Nightbitch opens two years after the unnamed, thirty-seven-year-old artist and mother who refers to herself as Nightbitch has given birth to her child. She’s over the hump of the newborn phase, made it through the most common window for postpartum depression, and her baby is now self-sufficiently holding up his own head and eating solid foods. But also by this point her husband has been travelling for work 22 of the last 24 weeks, and Nightbitch has long ago abandoned her art as well as her “dream job” at a community gallery in a small Midwestern town. She finds her choices have landed her in “the life she both wanted and didn’t,” where she is “no longer well rested, well fed, well.”

What stretches in front of Nightbitch are the liminal hours of mommytime, where the attention a child demands is more of the pot-banging variety versus the keep-him-alive vigilance that feels important. Gone are art and inspiration, and left in their place is her son, a person who doesn’t share her interests and puts his needs first: “He was her only project. She had done the ultimate job of creation, and now she had nothing left.”

As Nightbitch realizes she’s living a life she doesn’t recognize—one without art or a sense of identity—her body joins the defection. Hair starts growing like patches of fur on her neck. There is a lump at the base of her spine she is sure is a tail, but that her husband dismisses as a cyst. Four new “nipples” appear on her torso. As her symptoms worsen and she grows more and more convinced she’s turning into a dog, it’s not only her body that betrays her but “her sense that society, adulthood, marriage, motherhood, all these things, were somehow masterfully designed to put a woman in her place and keep her there . . . And once she was stripped of all she had been, of her career, her comely figure, her ambition, her familiar hormones, an anti-feminist conspiracy seemed not only plausible but nearly inevitable.”

With such a conspiracy in place, such surrendering of your place in the world, what’s a woman to do but take a dump in her awful neighbor’s yard, kill a rabbit with her teeth, sleep until she’s finally rested? To acknowledge her flame of rage as “that single, white-hot light at the center of the darkness of herself.”

It’s this banality of mom-life in conjunction with Nightbitch’s actions as a dog that captures the absurdity and loneliness many mothers feel. At one point, contemplating the other moms with their “plastic baggies of snacks, on the way to sniff a diaper” who seem content to just raise children, Nightbitch wonders, “maybe [they] didn’t need to be fulfilled in the way Nightbitch herself needed it?” But of course many other mothers feel just as angry and crazy and isolated as Nightbitch, and she finds it nearly incomprehensible so much of the population is walking around just existing this way. It’s almost as incomprehensible as thinking about how some people grow other people inside their bodies.

The commonplace and miraculous collide over and over in the novel. What could make a mom more ho-hum than being a good mother, but that’s just what Nightbitch is for the child she has. They play by “doggy rules” where she puts him to sleep in a kennel and takes away his binky, not because big boys don’t have binkies, but because dogs don’t. While their behavior in public might look unconventional, it’s what her child needs and she’s able to give it.

Even her relationship with her husband appears both mediocre and a marvel; millions and millions of people are partnered across the world, yet think what a miracle it is to feel truly known by another. Early on, Nightbitch’s husband says to her, “You always think something’s wrong with you,” and he says it “pleasantly,” an adverb that had my own hackles up at his dismissal of his wife’s concerns. But like many things in the book, the words and the way they’re said will come to mean much more. He truly means this “pleasantly”; he means it not as a dismissal but as a reminder, a way of helping her through this anxiety.

Beginning the novel, I admit: I wanted answers. Is Nightbitch turning into a dog or not? Is the alpha mom of the mommy group really a golden retriever? Can all of this be explained through “mythical ethnography”? Yoder seems to recognize that parenting and art rarely give moms or readers exactly what they want, and that if you embrace the experience, they can give you something much better, and much more meaningful, than you were ever able to anticipate.

Rachel Yoder (@RachelYoder) is the author of the novel Nightbitch (Doubleday, 2021). She is a graduate of the Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program and also holds an MFA in fiction from the University of Arizona. Her writing has been awarded with The Editors’ Prize in Fiction by The Missouri Review and with notable distinctions in Best American Short Stories and Best American Nonrequired Reading. She is also a founding editor of draft: the journal of process. She now lives in Iowa City with her husband and son.

Erin Flanagan (@erinlflanagan) is the author of the novel Deer Season (University of Nebraska Press, 2021) as well as two story collections. She is an English professor at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Learn more at erinflanagan.net.