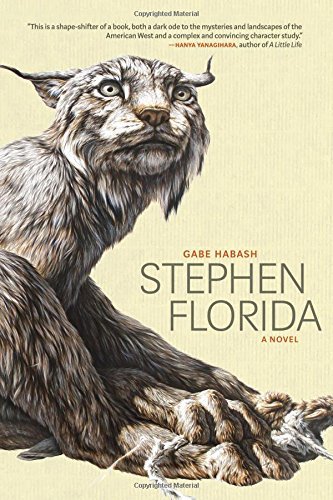

Where the Meat Is: On Gabe Habash’s Debut Novel Stephen Florida

Stephen Florida

Coffe House Press

June 2017

ISBN: 978-1566894647

304 pages

reviewed by Elliott Turner

As a monk may fast in penance, Stephen Florida wants his championship “bad enough to starve for it.” He has to be 133 pounds at weigh-in before a meet. He dines on broccoli and celery, allows himself to drink only “two allotted cups of skim milk.” His “midnight snack” is “roasted zucchini and squash.” When the mother of his only friend, Linus, comes to visit, she prepares eggs with olive oil, sans salt and butter. “Under two hundred calories total.”

Gabe Habash’s debut novel of the same name, Stephen Florida, will lure you into the depths of his mania. Set in a small North Dakota town, the reader follows the title character, a college senior, on his quest to win a wrestling championship. Yet this story is no quaint campus novel, nor another ode to sport. Rather, it’s a character study and a rocky bildungsroman.

The novel is written in the first person, and Stephen is not shy with the reader: He candidly shares his thoughts, and the tone is sharp. The style is confessional but never sentimental. From the outset, we know something is amiss. Amidst macho posturing and “I will win” thoughts, Stephen admits to serious flaws. “I keep things to myself,” he says on the second page. “I’m quick to anger, which is something I got from my dad.” He may be a senior on the wrestling team, but he is no leader. At one point, he declines to give the team a pep talk, instead thinking, “I look out for myself and that takes all my effort and all my time.”

The small North Dakota town where Steven goes to school is a dark, dreary place. Stephen himself observes that, “the buildings of Oregsburg are nothing but shadows in the week after daylight savings.” He often feels isolated: “[There’s] absolutely no noise at eight o’clock at night, no one outside walking, and it creates the illusion that you’re alone.” He succinctly notes that, “Five months, a winter, can be an oppressive and long thing.”

Religious themes are hinted at throughout the book. Sometimes overtly, sometimes subtly. Stephen claims to like his desolate surroundings because he is “on a one-lane road” and wants “no distractions.” He admits to not knowing much about the lives of the Saints, but feels his life is “exactly like what their lives were like.”

In the first part and in the denouement, Stephen wrestles with aggression, skill, and strategy. Still, you don’t have to know anything about wrestling to enjoy the book. As Habash himself noted in an interview with The Paris Review, a novel can include sports, but can’t rely on them.

Habash’s prose captures both the good and the unsavory aspects of competition. Stephen relishes the intimacy of wrestling, a solitary sport that involves grasping and clasping and physical proximity. For example, Stephen explains the technique of “shrimping,” where you hook and yank on your opponent’s head. The wrestling scenes bristle with energy, as Stephen explains his strategy in real time. “He shows his shell to me, I’m trying to turn him over and get to that sweet underbelly, where the meat is.”

Cheating is prevalent in wrestling, and Stephen shares some underhanded techniques that involve groping another man’s undercarriage. No one on the Oregsburg team likes to spar in practice with teammate Paul Kryger, because “at least half the team’s had his fingers up their asses.” This illegal move is known as “checking the oil.” Later, Stephen wins a match after provoking his opponent with another illegal move, the “five-on-two.” You can do the math.

Still, the heart of the story is Stephen’s arrested development and latent self-reflection. He starts to develop feelings for Mary Beth from his Drawing class. She asks him a few times his plan for life after college, but Stephen claims, “I hadn’t thought that far ahead.” Later, she asks him “what’s behind” his desire to win a wrestling championship. He says he “wants to become [his] full self,” but quickly admits, “Isn’t that what I’m supposed to say?”

The story shifts gears when Stephen suffers an injury at the end of the first part and has to rehab apart from the team. Without wrestling, his personal failings are laid bare. His friendship with Linus grows strained, then Mary Beth moves away to Michigan for a job. He calls her incessantly even though she seldom picks up. When she does, she suspects he only calls her because he’s lonely. She airs her grievance that, “if I didn’t pick up, it wouldn’t make much difference in the long run.”

Later, they each drive eight hours to meet at a diner, but the awkward and tense encounter ends with a mere kiss on the cheek. Stephen asks himself during and after, “why isn’t this working?”

Habash’s audacity pays off in part two of the novel, when the narrative structure shifts from short, unnumbered chapters to episodic vignettes similar to Valeria Luiselli’s Los Ingrávidos and Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. The pacing reflects the discombobulation of Stephen on morphine, as well as the tedious, almost empty days as he battles depression. He tries crossword puzzles for a day; he tries drawing sketches. Some vignettes are barely more than a single thought: “I can’t believe I used to be scared of dying. What a relief that will be.” He boasts, “I have figured out a way to make time pass faster is to sleep a lot,” only to realize soon after, “A few nights and days stocking up on sleep makes you restless.”

The third act reverts to conventional short chapters where Stephen recovers to compete in the national championship. Yet the return to the grind of wrestling comes with a new awareness and a sense of emptiness. The denouement leans more heavily into a traditional sports-narrative convention. Cue Rocky-style montage: athlete trains hard, athlete competes for trophy. But rather than full-throated triumph, this novel ends abruptly on a melancholic note. Somehow, the finale is both startling and expected.

Stephen Florida was billed as The Art of Fielding meets Foxcatcher, but this wrestling novel could not be more different than Chad Harbach’s baseball tome in plot and style. While Harbach juggled primary characters and major story arcs, Habash’s singular focus is Stephen and Stephen’s obssession. The Art of Fielding hummed along at a pleasantly slow pace, whereas Habbash throttles the pace of Stephen Florida, speeding up in the wrestling scenes and in the entirety of the second part of the book.

A more apt comparison would be Don DeLillo’s End Zone. Both books include a rambling first-person narrator, although unlike the solipsism of Stephen, Gary Harkness, the protagonist in End Zone, looks beyond football and waxes poetic on topics such as nuclear war and civil rights. The dialogue in Stephen Florida is not quite as sharp as End Zone—one speech from Stephen’s coach feels particularly unrealistic—but often enough Habash is poignant and funny.

While Stephen’s brusk voice may grate on some readers, his personal growth over the course of the novel makes this a rewarding read. Stephen’s wrestling career is exemplary, but his personal life is a cautionary tale: Is his singularity of focus a springboard to success or a kind of mania? Maybe it’s both. But at some point, no reward is worth such a degree of sacrifice.

Elliott Turner studied political science at Emory University. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Guardian, VICE, Fusion, Vox, Queen Mob’s, The Atticus Review, Transect Mag, & others. He is the author of The Night of the Virgin. He lives in Texas with his wife and three children..