In a Downward Spiral: A Review of Carlos Manuel Álvarez’s The Fallen (translated by Frank Wynne)

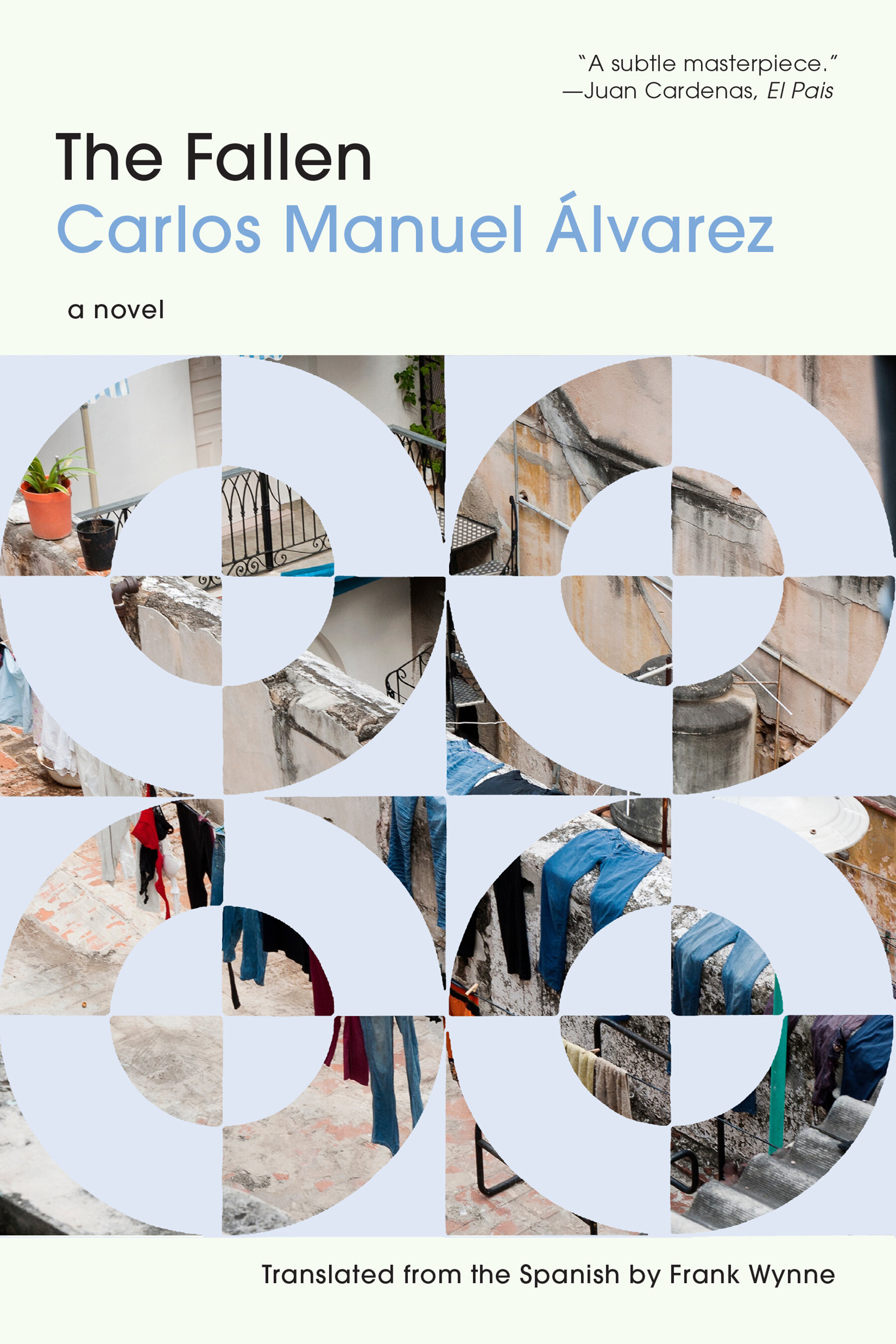

The Fallen

Carlos Manuel Álvarez

Translated by Frank Wynne

Graywolf

June 2020

ISBN: 978-1-64445-025-3

160 Pages

Reviewed by Gillian Esquivia-Cohen

A recurring nightmare haunts the father in Carlos Manuel Álvarez’s novel The Fallen. In it, he is driving into the future. Along the way, he passes all the heroes of the fatherland: Marx and Engels, Lenin and Che Guevara. They push wheelbarrows of hardened cement and bicycles with flat tires or stick out their thumbs, desperate for a lift. With their eyes, they plead for the father to stop the car and pick them up, but he drives on. On his way back, he passes the sad procession again. “The pain of it!” he says. “All these brilliant minds leaving just as I arrive. That is the nightmare, that is the future.”

The Fallen is a portrait of a society in a downward spiral as told through the story of one family. Composed of five sets of monologues by each of the four family members, the novel’s structure is likewise a spiral, with each section circling the story’s central axis: the mother’s illness. As the story progresses and the secrets, lies, and omissions accumulate, the tension increases until the reader feels they are being sucked down a drain.

Through the four characters, Álvarez opens a window onto a cross-section of contemporary Cuban society. The father, a die-hard Communist who considers himself a soldier for the Party, stakes his identity on upholding the values and ideals of the Revolution. Impaired by her illness, the mother struggles to find herself and her place as the illusion of her perfect family disintegrates. The daughter hustles to put food on the table which, as is common in Cuba, means stealing from the hotel where she works, while the son fulfills his obligatory military service, swinging between boredom and deep resentment toward his father who could have done more to provide them a decent life.

In less able hands, these characters could easily have become clichés, especially given how close some come to Cuban cultural archetypes (such as that of the mindless Party foot soldier). Yet Álvarez’s characterization reveals deep compassion for all four family members—despite how ugly their behavior sometimes is—and each character lives on the page as a complex individual born of a particular context.

In his interview with Álvarez, the Spanish novelist Andrés Barba points out that, although the characters are often unlikeable, the novel suspends moral judgement. The author does nothing to help the reader decide how they should feel about the son, who often acts like a spoiled brat but also suffers the consequences of a childhood of extreme poverty, or the daughter who steals but whose theft keeps hunger away from the family’s door.

Unfortunately, the English translation by Frank Wynne departs from the original Spanish in ways that change the characterization of the family members, especially the son, Diego. The translation has several simple errors. To take one example: it renders “donde no sin estereotipos, claro está, se explican nuestros costumbres” as “that explains our customs—without stereotyping, of course” when the phrase actually means the exact opposite. To take another: it includes an unjustified addition of the adjective “stupid” before what in the Spanish text is the neutral word “idea.” In addition, on one occasion, the translation omits an entire paragraph, one that deeply impacts Diego’s characterization and the development of the novel’s themes.

This paragraph occurs in Part III, when Diego is explaining the two issues he has with his father revealing the inexistence of the Three Wise Men (who bring children presents on Christmas) when he was still young: “The first is that if a father is going to deprive you of the Three Wise Men, it is his responsibility to take their place, not leave you orphaned at the age of six or seven, the way [the father] did me.” Diego continues on to describe the effects of that orphanage. Then, in Wynne’s translation, the following paragraph jumps right into the second issue, namely, the replacement of the mythical Three Wise Men with the father’s Communist ideology. However, Álvarez’s original text includes the following, which I have translated, between those two paragraphs:

I don’t want to say anything in particular with this, but I was a kid that would go up to the bathroom mirror—fortunately, we at least had a bathroom mirror—and stay there for several minutes, looking at himself, surprised that the boy reflected in the mirror was the boy he was, completely estranged from himself, trying to understand or digest what it was that was reflected and how that reflection was more his than any other thing he owned, or how it was all he was, all the infinity of his daydreams, his silly ideas, and his tender thoughts, all the dizzying sum of total insignificance that, from the time he is a boy, man is, summarized in that profile where I, understandably, could not fully recognize myself.

This paragraph echoes the mother’s own inability to recognize herself in the mirror in Part I, calls back to the father’s musings on chirality and the dangers of reflections in Part II, and ties into the body/self dialectic developed throughout the novel. It is, in other words, a significant passage for the novel’s themes and one that shows the reader another side of the son. In omitting this paragraph and making a number of smaller editorial changes that alter characterization, Wynne’s English translation flattens Diego, bringing him dangerously close to the stereotype the novel’s author so carefully avoided creating. While I cannot recommend Los caídos highly enough, Wynne’s English translation requires revision before it can do justice to Álvarez’s elegant novel.

Note: When I reached out to Graywolf about these translation issues, they put me in touch with Álvarez’s editor, Ethan Nosowsky, who said the missing paragraph was an oversight. He expressed regret at the error, which he said would be corrected in future printings. He also said Graywolf would review the translation for other issues.

Carlos Manuel Álvarez (@EspirituCarlos) has contributed to the New York Times, El País, BBC World, and the Washington Post. In 2017 he was included in the Bogotá39 list of the best 39 Latin American writers under 40. He divides his time between Havana and Mexico City.

Gillian Esquivia-Cohen (@Yilis6), a dual citizen of the United States and Colombia, is a writer and translator. She is currently an MFA candidate at the Institute of American Indian Arts, where she is working on a novel.