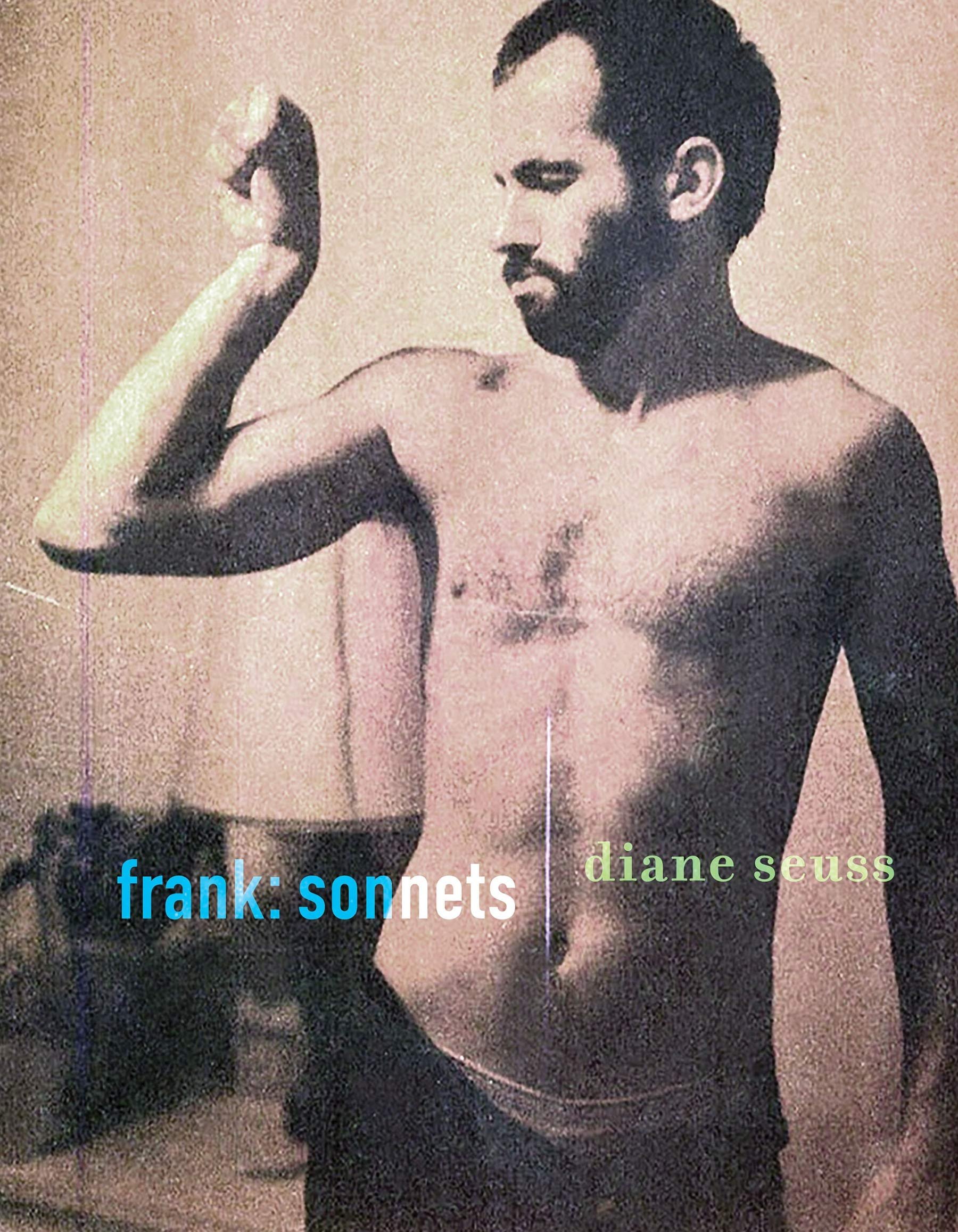

A Reinvention of Form, a Kind of Monomyth: A Review of Diane Seuss’s frank: sonnets

Writing a review some months after a critically acclaimed book has been released can be a challenge. Generally, all the good words have been taken, and you have to claw through the ground looking for an unused noun, surreptitiously create a new adjective out of dried grass, an errant dandelion puff, and some spit. This is particularly so with Diane Seuss’s highly regarded frank: sonnets, which, though well-named, doesn’t provide a true sense of the exhilarating ride ahead.

In poetry we often talk about form and content, how one informs the other, or in some cases, conflicts to create something new; the irritation of the sand that births a pearl, or the shoe edge that creates a callus. In that sense, the use of a sonnet, especially in contemporary poetry, can be an ironic commentary on past forms—that of academy, of patriarchy; of sharp lines, narrow cages, and impenetrability.

But perhaps it’s also something else. The base of the sonnet, the essential rhythm of fourteen lines—ignoring traditional edicts around syllable counts and meter—is reminiscent of the vehicle we’re given, this brief page of a life. Each of us have fourteen lines to write: in ink, carbon, sweat or blood; entangling DNA and memory, channeling who and what was or never will be. Perhaps there will be a volta, a moment of reflection, a turning to something new. Or maybe the end will come unexpectedly, allowing the page the last word, rather than the author.

In the first sonnet, Seuss informs us: “I’m a little like Frank O’Hara without the handsome / nose and penis and the New York School and Larry / Rivers.” This both inserts the spirit of the extemporaneous style of O’Hara, as well as a contrast to a female poet who experienced misogyny and worse, rather than the kind of support that the idealized (male) 1960s poets and painters offered each other. Seuss’s speaker is far larger than any categorization: the subject matter varies; the syntax shifts from unpunctuated streams to complete sentences; and her improvisational, conversational tone feels both novel and familiar at the same time.

I was not a large child, though large in silence, learned

from pods and brambles and cattail’s velvet fruit. Like

the world, which began as a pea-sized notion under

the mattress of an oversensitive girl, I grew vast, too vast,

The poems are grounded in real events, people, and many losses—a beloved who died of AIDS, her son’s addiction, a difficult marriage, her challenging childhood along with a few well-known members of the punk scene thrown in—but also echo the fables and mythologies we use to light our paths, to shape our narratives, our once-upon-a-times. “We all have our trauma nadir, the umbilicus from which / everything originates and is tied off and turns black / and the cord eventually falls away,” Seuss writes. She is especially candid about breathtaking losses that are more impactful for the lack of melodrama. There are high stakes and tension throughout the collection, and our poetic maestro also seeds the ground with humor, beauty, and the kind of small details that are the subtle ingredients of what constitutes a life and a poem.

As this is about many of Seuss’s passions, it’s understandable that there are a number of ars poetica pieces—about poems as living entities; perhaps the only kind that may be silenced, may lie dormant, yet never die. These poems about poetry often examine how the art form may exist out of the hands of the poet herself, as if she were collaring a wild animal that will not be tamed: “Do you see / how I persist in telling you about the flowers when I mean to describe the rain?” Seuss is leading us on a kind of monomyth, much in the same way this collection reconfigures the sonnet and poetry overall. The transformative aspect of this hero’s journey is less about a victory or even a distinct conclusion than an ongoing story. As complete as this collection is, one doesn’t feel that Seuss is done with the sonnet or the sonnet with her:

The sonnet, like poverty, teaches you what you can do

without. To have, as my mother says, a wish in one hand

and shit in another.

[…]

Poverty, like a sonnet, is a good teacher. The kind that raps your

knuckles with a ruler but not the kind that throws a dictionary

across the room and hits you in the brain with all the words

that ever were.

She’s fearless in her revelations but, like a poetic Salomé, amidst glimpses of bareness and vulnerability the reader is aware that there’s more that is shielded and not for our eyes. Some of these sonnets are one run-on sentence without punctuation or speckled only with commas that offer brief pauses to allow you breath, which you’ll need as they will have you gasping with their simplicity as a hot knife through butter, or a sharpened skewer directly into your heart.

Poetry, the only father, landscape, moon, food, the bowl

of clam chowder in Nahcotta, was I happy, mountains

of oyster shells gleaming silver, poetry, the only gold,

or is it, my breasts, feet, my hands, index finger,

fingernail, hangnail, paper cut, what is divine,

Seuss’s sonnets go beyond questions of tradition or contemporary poetics. They are a reinvention that’s far greater than the sum of their parts. Deeply personal, brutally direct, funny, painful, and always wondrous, sometimes it seems the only thing that makes these sonnets is fourteen lines per page. Yet they are sonnets because the poet, in the full command of her power, tells us they are; there need be no more proof than her word, and her words. Singly, each one is memorable. Together, they build a narrative that’s confident, flexible and unforgettable. For all the range of emotions that Seuss mines so viscerally, there are also stunning lyrical segments:

…the sunset, oh, ragged and bloody as a piece

of raw meat in the jaws of some big golden carnivore,

and I cried a little, for none of it! none of it will last!

None of it will last, which is both the heart of the sonnet, as well as its turn, and conclusion. Our lives won’t last, though their echoes will as long as those who live still recall us, and this collection will, long after the final page is turned.

Diane Seuss (@dlseuss) is the author of frank: sonnets, Still Life With Two Dead Peacocks and a Girl, Four-Legged Girl, a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and Wolf Lake, White Gown Blown Open, winner of the Juniper Prize. She lives in Michigan.

Founder and Editor-in-Chief of Nowruz Journal, a periodical of Persian arts and letters and Editor and Senior Strategist at Chicago Review of Books, Mandana Chaffa’s (@recycledgiraffe) writing has appeared in a variety of publications and anthologies. She serves on the boards of the National Book Critics Circle and The Flow Chart Foundation. Born in Tehran, Iran, she lives in New York.