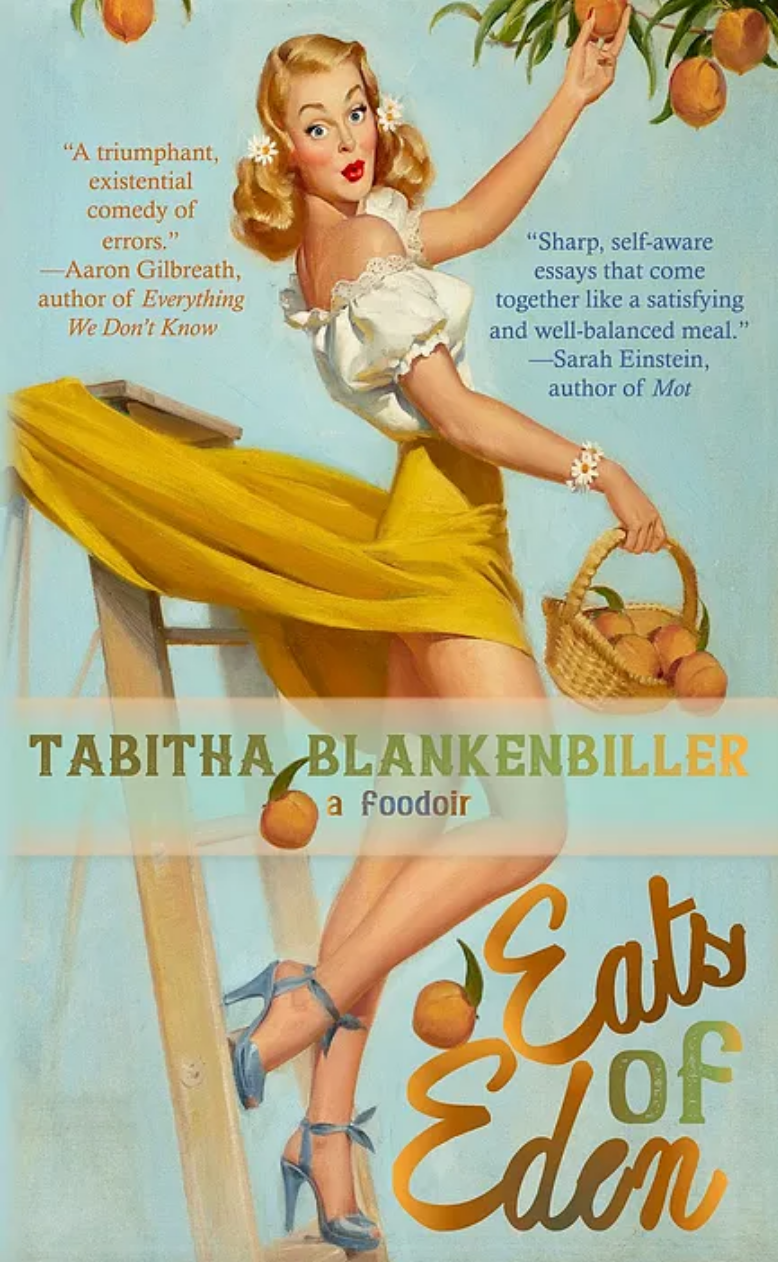

EATS OF EDEN: A Conversation with Tabitha Blankenbiller

Tabitha Blankenbiller is the kind of writer who can cook up an essay that’s equal parts delicious self-reflection and nutritious nourishment for understanding broader life experiences. Her work has been published in a variety of venues, including The Rumpus, Alternating Current, Barrelhouse, Luna Luna Magazine, Catapult, and here in Split Lip Magazine. Her debut essay collection, Eats of Eden, is out in March 2018 with Alternating Current Press. Imagine The Great British Bake Off meeting Sex and the City somewhere in the Pacific Northwest (with a quick detour to Disneyland), and you get a good sense of what awaits you in Eats of Eden. Blankenbiller talked with me about her book, the writing process, and learning how to let go of some things in the process of growing up.

Hillary Moses Mohaupt: Your book ostensibly covers a year in which you’re writing a novel that’s based in large part on a childhood friendship. Your training is in creative nonfiction rather than fiction. How did you approach writing this collection of essays differently than how you were approaching the novel? Did it matter that you were working on both?

Tabitha Blakenbiller: There’s some strange meta-antics happening during this book for sure. Essentially what happened was that I had been working on a memoir in some form or another (a thesis, a book proposal, a full manuscript) for half a decade and I was crashing and burning. My memoir wasn’t going anywhere, and I was beginning to believe what all of the editors that passed on it were saying that no one wanted to read a coming-of-age memoir by a nobody.

That was difficult feedback because it’s kind of a chicken-in-the-egg situation, as in I can’t become a somebody if nobody ever publishes my book, and so on and so on for all artistic infinity. I decided then that I was going to take a break from memoir-writing and try to write a kind of alternate reality, Sliding Doors semi-autobiographical novel.

I was digging into that project in earnest when Alternating Current Press asked if I wanted to write an essay collection based on a food-and-writing column that I’d created for them, which was about trying to create a book. Now we have a whole new egg, new chicken. Writing a book about writing another book. Kind of like now the basket is overflowing with all these goddamn eggs.

I am absolutely not a fiction writer. The only fiction I’ve ever successfully published is super parody Food Network fanfiction. I spent much of the time I was writing the novel, Emily and Julia, wrestling with what was believable. Would anyone believe these two women were breathing, actual people? Did their actions make sense? Was I giving their friends and family members enough agency outside of their issues and intersections? I worried constantly that people would see through me and know that I was writing about a woman who commuted in Seattle by bus every day when I have never, ever once taken a city bus in my life. I love a good novel and believe in them full-heartedly; I simply don’t know how to do that.

When I was writing the memoir, I had fears that traced back to my history of failures and those questions over commercial viability, but if I could hold those at arm’s length long enough, the work felt inherent. Essay-writing is the natural fit for the way I work through my emotions and process the world. I can’t change how famous I am or what is trending in sales. This is how and what I write, and either it’s going to be seen or it isn’t. Pretending to be anything else isn’t going to advance my cause.

HMM: How is your writing process different from your cooking process? Do they feed each other (no pun intended!)?

TB: I think the trade-off with writing versus cooking is that the cooking is much more ephemeral. There is the wonder and joy of almost instant gratification (definitely instant in comparison with the gratification for a piece of writing), as in you get to Instagram and dig into something beautiful you make as soon as you’ve finished creating it. Your pineapple upside-down cake doesn’t need to sit in a Submittable queue. The flip side of that is, as soon as the dishes are done, it’s gone. It only existed for a short period on the plate, a moment on the tongue, and its legacy is only a memory to the limited company around your dinner table. On occasion you can recreate a perfect dish, but often it was a particular moment, a confluence of luck and accident, that is impossible to reconstruct.

This happens in writing too, but it’s easier to go back and see what you’ve done before. You can retrace your steps with a concrete body of work.

HMM: Every essay ends with a recipe related to, or featured in, the preceding chapter. Tell me about the process of writing or compiling those recipes. Did you test them for the book, à la Cooks Illustrated?

TB: I don’t consider Eats of Eden to be a cookbook, because I’m not a chef. These are recipes that I love that I’ve cooked and tweaked from my favorite cookbooks and magazines and TV shows. It’s a demonstration of how I feed my body and creativity, so yes. The recipes have been made by me quite a few times in most cases.

HMM: This book is about food, but it’s also about friendship—the ones that last, and the ones that don’t, the ones we have in childhood, and the ones we maintain as adults. How did writing this book change your philosophy? Do you think we approach friendships differently as adults and over the course of adulthood?

TB: I think that the whole book was a process of letting go of the ideas of what was “supposed” to happen. As in, I was “supposed” to have a book that my agent sold. I was “supposed” to finish Emily and Julia from one Oktoberfest to another. And when it came to friendships, I had to concede the idea of a relationship that would last a lifetime. I thought best friends were “supposed” to be forever, and maybe for some people, they are. That’s not what happened for me. I feel that I came away from the book realizing that the dissolution of my friendship with my best friend Claire wasn’t a personal failure, it was personal growth. Friendships become so difficult in adulthood. We make so many tectonic shifts from 19 to 25 to 33. It’s tough to keep track of ourselves, and what we want and need, let alone those around us. Some people get lucky and make similar choices as those they’ve grown up with, or met in early adulthood. I didn’t. I took a hard hairpin turn into “fuck this, I want to be a writer” land. When you rewrite the fundamentals of what you want out of life, you’re going to take some losses.

HMM: Choosing to go pursue an MFA at Pacific University was part of that hairpin turn, right? What has stuck with you from your time at Pacific? What do you wish you’d known before your first residency?

TB: It’s been so long now! Oh my god. I remember feeling so old and “grown up” when I graduated at the ripe age of 27. I had this whole writer deal all figured out, let me tell you.

I think what I would try to tell her is that it takes a long fucking time to become a writer. A. Long. Fucking. Time. It takes a long fucking time to hone your instincts, to know with confidence when a sentence or paragraph or entire piece isn’t working—and to develop the conviction you need to stand by your work when you know it is, in the face of those who disagree with you and pass it up. It takes a long fucking time to read widely and discover what is possible, and absorb those voices and structures into your fiber so it flows naturally from your fingertips. And it takes a long fucking time to live a life to write about, and to develop the experience and wisdom to shape what you’ve seen and experienced into meaningful work. I would tell her that this book she wants so badly will be more difficult than she can imagine, and that no, she’s not clever enough to suss out a shortcut.

But she was a real self-assured pain in the ass, so I know she never would have listened to me anyway.

HMM: If Martha from The Great British Bake Off were reading this, what would you like to her know?

TB: It’s not who wins, it’s who we remember.

HMM: What are you working on now?

TB: Another essay collection, centered around my favorite place in the whole wide world.

So no, it’s not a retrospective on Tucson.

Hillary Moses Mohaupt is a listmaker: she’s a writer, social media editor, pie baker, Midwestern ex-pat, and francophile. Her work has appeared in The Writer’s Chronicle, Brevity’s blog, Lady Science, Breathe Free Press, Distillations, and Horizons. She’s the social media editor for Hippocampus Magazine, and she’s one half of The Screen Sirens, a podcast about women and social justice in classic Hollywood films.